Gadara or Umm Qais first appears in the historical records shortly after the conquest of the region by the forces of Alexander the Great in 333 BC. Alexander s successors, the Ptolemies, made the site a frontier or border the meaning of the toponym - with their perennial rivals, the Seleucids, who were based in Antioch, north Syria.

The Roman general Pompey conquered the region of south Syria in 63 BC. Shortly afterward, Gadara minted its own coins and was one of the leading cities of the Decapolis. Most of the standing Roman architecture at Gadara (Umm Qais) was built in the second century AD. At this time, the baths of Harnath Gader, located below and to the northeast of the city, were also built.

Christianity spread slowly among the people of Gadara in the first three centuries AD. During the reign of Diocletian (AD 284-305), Zacharias, together with Alpheios, suffered martyrdom in AD 303. By the early fourth century, however, Christianity was firmly rooted in the city and Bishop Sabinus of Gadara participated in the Council of Nicaea in AD 325. The victories of Islamic armies over the Byzantine forces in the first half of the seventh century brought north Jordan under Muslim controls. In their wake, there was a peaceful transition from Byzantine to Islamic rule at Gadara. The city continued to prosper until earthquakes destroyed many of its structures in the seventh and eighth centuries.

The site was rediscovered in the 19th century, and the Department of Antiquities s of Jordan, established in 1928, began excavating there in the 1930S. Major excavations on the part of the German Protestant Institute for Archaeology in cooperation with other foreign groups began in 1974.

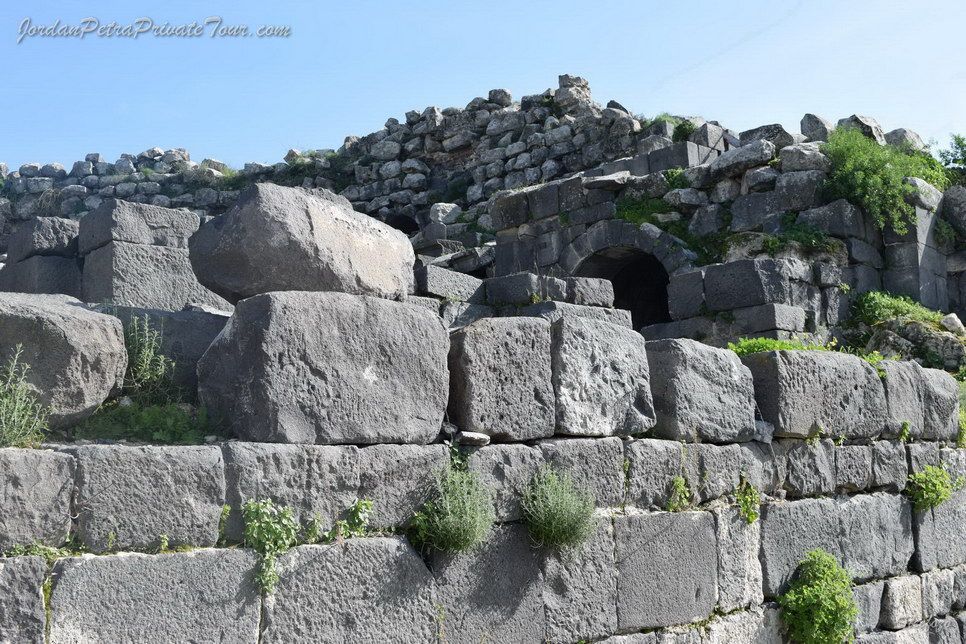

The ruins of ancient Gadara cover an area of ca. 1600 m from east to west and ca. 450 m from north to south. The area of the Greco-Roman acropolis now lies beneath the late-19th-century Ottoman village. It is from this location that the best views of the site and the surrounding regions are possible.

There is much for the pilgrim and/or tourist to see in the ancient city. For example, there is the Eastern Necropolis, the two theaters, the vaulted shops and the colonnaded main street (the decumanus maximus: the public baths and the nymphaeum, the remnants of the western gates with their towers, and the north mausoleum, at which a Greek inscription, dated to AD 355/356, reads: "To you I say, passerby: As you are, I was; as I am, you will be. Use life as a mortal."

The decumanus divided Gadara into a small northern and a large southern sector. Smaller roads would have intersected with this main street to form rectangular city blocks. The main north-south street of the city (cardo) has not been identified to date but it is thought that it intersected with the decumanus near the nymphaeum. Beneath the street was an extensive subterranean drainage system that supplied the city with fresh water. The street itself was flanked by sidewalks and paved with basalt slabs. At least in the western part of the city, the street was lined with columns.

Our main interest here is in the ecclesiastical structures on the Church Terrace and the Roman Mausoleum, Christian Crypt, and Five Aisled Basilica. Both areas seem to be associated with pilgrimage activity.

The Church Terrace

A large colonnaded terrace (UTM coordinates: 0751197E/3616545N; elev. 360 m)" is located north of the western theater. There are two churches on it. They replaced an earlier Roman public building, probably a colonnaded hall or market basilica.

One of the churches is square with an octagonal interior and a large courtyard. A square, stone-lined depression in the eastern section of the interior of the octagon was the church s altar area, or bema. It was originally set off from the central domed octagonal room (the nave) by marble screen slabs or a chancel screen. A stone-lined tomb was found within the altar area. The corners of the square church are in the form of semicircular apses. Its roof was probably in the form of a semi-circular dome.

The church had three entrances. It was built in the first half of the sixth century and destroyed by an earthquake, perhaps in the eighth century (Schick 1995: 478).

The second church, located immediately to the south of the square one, is smaller. It is a three-aisled basilica with a single apse. It is later than the square church and was built in the middle or the second half of the sixth century AD.

The excavators found four tombs and five reliquaries, containers in which relics were placed, in the churches. These finds indicate the importance of the complex from a Christian viewpoint. They may indicate that the site was one to which pilgrims came; in fact, the tomb in the square church may have been the grave of a venerated martyr.

Roman Mausoleum, Christian Crypt, and Five-Aisled Basilica

A five-aisled basilica (UTM coordinates: 0750575E/3616513N; elev. 336 m) is located in the lower city of Gadara, west of the acropolis. It covers the area on top of a Roman underground mausoleum and a Christian crypt extending towards the east. On the basis of the structural layout of the plan, one must consider that the Roman underground burial chamber and the crypt were deliberately adopted by the early Christian community of Gadara in their worship. The whole complex lies close to the main street to the southwest of the southern circular tower of the Tiberias Gate.

The early Christians of Gadara built an underground crypt adjacent to and east of the Roman mausoleum. This burial place was dedicated to a prominent local saint, maybe the Gadarene Deacon Zacharias, who suffered martyrdom in the years of the Diocletian persecutions (Al-Daire 2001: 553). His apse-framed tomb was considered a holy place and became a focus of early Christian pilgrimage. For this reason, one would assume that the whole complex, including the Roman mausoleum and the superstructures of the underground sepulchral buildings, had a memorable character. The rest of the crypt was used for the burials of other notables of the early Christian Gadarene society, who were buried close to the venerated corpse.

Weber, the excavator of the complex, concludes that the basilica, together with the underlying crypt, was constructed in the first half of the fourth century AD (1998: 449; see also Al-Daire 2001: 560). The last burials in this privileged area were put there in the late fourth or the first half of the fifth century AD.

The five-aisled basilica, which is almost square, measures 21.50 (EW) x 20.IO (N-S) m. It is oriented east-west with an entrance hall and a large open air colonnaded courtyard (atrium) in the west, which is almost square as well, measuring 26-47 x 26.00 m. The complex was framed by paved passageways along its southern and western facades. The northern wall of the complex was located ca. 30 m from the east-west running Main Street. A minor, perpendicular roadway would have connected the complex to the main street on the west.

The apse of the basilica was constructed on top of the semicircular base of the crypt, where a local saint had been buried. Its purpose was to frame the central tomb of the early Christian cemetery. The apse was framed by a chancel screen, of which the remaining walls were found in situ.

The central nave of the basilica is situated exactly atop the Roman mausoleum. A circular opening in the center of the nave looks down into it. The church s nave was separated from the lateral aisles on both long sides by an arcade consisting of seven columns each. The adjacent areas to the south and north were subdivided by one row of pilasters corresponding to the colonnades of the central nave. Thus, the northern and the southern sections of the church hall were divided on both sides into two lateral aisles. The main entrance to the church was from the west and gave access to the church s central aisle. On both sides of the apse, two doors gave access to the aisles immediately to the north and south. The baptistery was located in the south-eastern corner of the complex.

The original fourth-century-A church was converted into a smaller chapel after its sixth-century renovation. The existing mosaic floor, now in the Umm Qais museum, dates to the sixth century AD.

The church was used over a long period for Christian liturgy. The first substantial alteration of the architecture was most likely executed when the basilica was partially destroyed by an earthquake in the Late Byzantine or Early Islamic periods. Despite its condition, Christian liturgy continued inside the building during the Early Islamic rule. It was probably transformed into a mosque during or shortly after the time of the Crusades.

Weber thinks that the entire complex, including the integration of the Roman mausoleum into the early Christian cult, "may perhaps be connected with details in the New Testament about the miracle of Gadara (Matthew 8.28)" (1998: 452; see also Al-Daire 2001: 559). Furthermore, he writes, that the Gadarene structure must have been dedicated for an outstanding event or person of the Bible or early church history. Despite the lack of inscriptions or other striking evidence, it should not be excluded, that a pilgrim church of this size was built on the spot, where Byzantine tradition recalled that Jesus had performed the miracle of the Gadarene swine (1998: 452).

(The Decapolis – Ten Cities are : Gerasa “Jerash today” in Jordan, Scythopolis (Beisan / Beth-Shean) in Palestine , Hippos “Hippus or Sussita” in Palestine, Gadara “Umm Qais” in Jordan , Pella in Jordan , Philadelphia or “Amman” in Jordan , Capitolio (Beit Ras ) in Jordan , Canatha or “Qanawat” in Syria, Raphana in Jordan, Damascus – Capital of Syria )